-

Herzlich Willkommen im Balkanforum

Sind Sie neu hier? Dann werden Sie Mitglied in unserer Community.

Bitte hier registrieren

Du verwendest einen veralteten Browser. Es ist möglich, dass diese oder andere Websites nicht korrekt angezeigt werden.

Du solltest ein Upgrade durchführen oder einen alternativen Browser verwenden.

Du solltest ein Upgrade durchführen oder einen alternativen Browser verwenden.

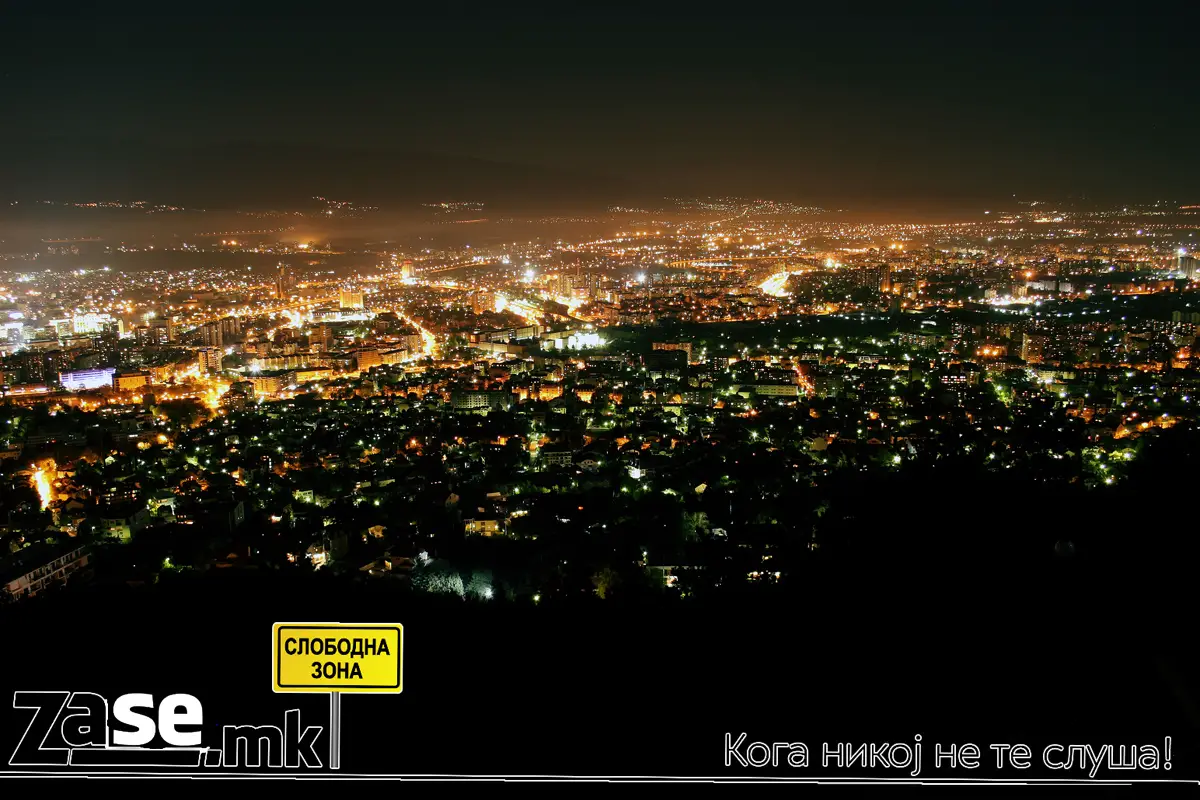

Скопје | Skopje | Shkup

- Ersteller _Hajduk_

- Erstellt am

Zoran

Μακεδоν τ

Special recognition for new Macedonian museum

Tuesday, 30 April 2013

Skopje-based Museum for Macedonian Struggle was a candidate for the Luigi Micheletti Award 2013 in the category of history and military-history museums, administered by the European Museum Academy (EMA).

The Museum said in press release Tuesday that in a competition of 21 top institutions from Europe, it was honored with a special recognition for the enthusiasm and achievements in preserving the national treasury, as an encouraging sign of the viability of European practice.

EMA Director and Chairman considered the Museum's presentation as rather innovative, saying that it may serve as an example to future candidates.

At a ceremony held in Bursa, Turkey, the Militärhistorisches Museum der Bundeswehr in Dresden, Germany, was announced as the winner of the 2013 Micheletti Award.

The Luigi Micheletti Award is the European prize for innovative museums in the world of industry, science and techniques. It is one of the leading activities of the Luigi Micheletti Foundation.

The criteria are concentrated on those aspects of a museum which – more than the quality of the exhibitions, of the building, etc. - contribute most directly to attracting and satisfying visitors beyond their expectations. Kenneth Hudson, the founder of the European Museum of the Year Award and the European Museum Forum, called it 'Public Quality'.

From the DASA of Dortmund, the first winner in 1996, to the TIM of Augsburg, the winner of 2011 Edition, the story of the Luigi Micheletti Award confirms that the concept of "museum's quality" is a reality from a changing, bur recognizable, face.

Tuesday, 30 April 2013

Skopje-based Museum for Macedonian Struggle was a candidate for the Luigi Micheletti Award 2013 in the category of history and military-history museums, administered by the European Museum Academy (EMA).

The Museum said in press release Tuesday that in a competition of 21 top institutions from Europe, it was honored with a special recognition for the enthusiasm and achievements in preserving the national treasury, as an encouraging sign of the viability of European practice.

Sie haben keine Berechtigung Anhänge anzusehen. Anhänge sind ausgeblendet.

EMA Director and Chairman considered the Museum's presentation as rather innovative, saying that it may serve as an example to future candidates.

At a ceremony held in Bursa, Turkey, the Militärhistorisches Museum der Bundeswehr in Dresden, Germany, was announced as the winner of the 2013 Micheletti Award.

The Luigi Micheletti Award is the European prize for innovative museums in the world of industry, science and techniques. It is one of the leading activities of the Luigi Micheletti Foundation.

The criteria are concentrated on those aspects of a museum which – more than the quality of the exhibitions, of the building, etc. - contribute most directly to attracting and satisfying visitors beyond their expectations. Kenneth Hudson, the founder of the European Museum of the Year Award and the European Museum Forum, called it 'Public Quality'.

Sie haben keine Berechtigung Anhänge anzusehen. Anhänge sind ausgeblendet.

From the DASA of Dortmund, the first winner in 1996, to the TIM of Augsburg, the winner of 2011 Edition, the story of the Luigi Micheletti Award confirms that the concept of "museum's quality" is a reality from a changing, bur recognizable, face.

Anhänge

Sie haben keine Berechtigung Anhänge anzusehen. Anhänge sind ausgeblendet.

Černozemski

Македон&

Zoran

Μακεδоν τ

Communist Architecture of Skopje, Macedonia – A Brutal, Modern, Cosmic, Era

Nate Robert in #Macedonia May 6, 2013 Comments { 20 }

Skopje, capital city of Macedonia, is a dream world for lovers of cosmic concrete communist-era architecture. There is a reason that no other city on Earth has as many examples of brutalist architecture. There’s no tactful way to say this – the abundance of magnificent structures, is all due to a catastrophic earthquake that killed over 2000 people, and destroyed more than half of the buildings in this ancient city. In 1963, Skopje was flattened. In 1965, Japanese architect Kenzo Tange was selected as the winner of an international competition to redesign, and rebuild the city centre.

Napier – the small New Zealand city where my travelling partner Phillipa was born, suffered a similar fate. The great quake of Napier in 1931 occurred right at the peak of the Art Deco movement. Napier was destroyed, and then rebuilt, all in the early 1930′s. As a result, the city can rightfully claim the title of “art deco capital of the world”. Back in Skopje, 1963, the architectural trend wasn’t art-deco, it was modernist, with a particular focus on concrete brutalism. Unlike Napier, Skopje has yet to capitalise on its architectural heritage. I would suggest a new tourist slogan – “Skopje – Brutalist Capital of the World”. Perhaps it’s not as catchy.

Examples of brutalist architecture - a style typified by geometric themes and raw concrete – occur all over the formerly communist area of Yugoslavia. In Zagreb, in Belgrade, and in nearly every small town, exist examples from this era. However, it is the legacy of Kenzo Tange, that makes Skopje so special in this regard. Locals are indifferent about memories of the Yugoslavia communist-era in general, however most people I have spoken to when visiting these buildings are familiar with Kenzo Tange. And whether they are particularly a fan of this style of architecture or not is beside the point – it’s clear that the positive impact Kenzo Tange had on the community of Skopje, in the wake of a devastating natural event, will not soon be forgotten.

The brutal home of the Skopje State Hydrometeorological Institute. Architect – Krsto Todorovski, 1975.

The brutal home of the Skopje State Hydrometeorological Institute. Architect – Krsto Todorovski, 1975.

Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music,1974.

Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music,1974.

Brutal students dormitory buildings “Goce Delčev” in Skopje, Macedonia. Architect – Georgi Konstantinovski, 1975.

Brutal students dormitory buildings “Goce Delčev” in Skopje, Macedonia. Architect – Georgi Konstantinovski, 1975.

Macedonian National Radio and Television building, Skopje. Architect – Kiril Acevski, 1971-1983.

Macedonian National Radio and Television building, Skopje. Architect – Kiril Acevski, 1971-1983.

Looking up inside Universal Hall, Skopje, Macedonia. Prefabricated by the Bulgarian company Tehnoeksportstroj, completed in 1966. A donation to Macedonia.

Looking up inside Universal Hall, Skopje, Macedonia. Prefabricated by the Bulgarian company Tehnoeksportstroj, completed in 1966. A donation to Macedonia.

And this is the part of the article where we deal with some problems of terminology. Macedonia, officially “The Republic of Macedonia” or “The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” depending on which international body you are speaking to, declared independence from communist Yugoslavia in 1991. The naming issue is telling, for a country whose government is seemingly hell bent on rebuilding its history (some people would say rewriting history), even the name of the country may not be final.

Due to a dispute with Greece, and in particular the Greek region just across the shared border also known as Macedonia, The Republic of Macedonia was admitted to the United Nations only with the provisional name of FYROM. But this soviet-esque abbreviation is already out of favor with many UN members. Apologies to Greece, but it appears the name FYROM will be going the same way as Rhodesia, The Dutch East Indies, and Upper Volta. To most people around the world, Macedonia, is Macedonia.

Brutalist, Modernist, But Not Communist Architecture?

Macedonian naming issues aside, there is another problem when referring to this style of architecture. Of course, it isn’t “communist architecture”. Kenzo Tange was certainly not communist, for a start. However, the fact remains that all of the architecture featured in this article, was indeed constructed during a period in which Macedonia was a part of communist Yugoslavia. I should also add that the Yugoslavian dictator Tito ruled his nation seemingly benevolently. There was no Iron Curtain in Yugoslavia, despite that this is the very region where the term originated. Much like China today, Yugoslavians were encouraged to be capitalist consumers. They didn’t suffer restrictions on leaving the country, as was occurring in much of the rest of Eastern Europe during this period.

Kenzo Tange and his Japanese team aside, the other architects of these structures may or may not have identified as communists, or socialists. The term is used these days, simply to denote a period in time. For westerners, the term communist architecture has come to denote the stark, efficient, cosmic, brutal, distinctive and unique style of Balkans area architecture that was often decidedly different from what was being built elsewhere. Personally, I think it’s a beautiful style. A venture into the interiors of any of these buildings will show that both form and function were frequently mastered.

Skopje State Hydrometeorological Institute. Architect – Krsto Todorovski, 1975.

Skopje State Hydrometeorological Institute. Architect – Krsto Todorovski, 1975.

News Publishing Agency “Nova Makedonija” building (no longer used by this agency). Architect Blagoja Kolev, 1981.

News Publishing Agency “Nova Makedonija” building (no longer used by this agency). Architect Blagoja Kolev, 1981.

Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music,1974.

Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music,1974.

Typical concrete detail on a communist-era apartment block in Skopje, Macedonia.

Typical concrete detail on a communist-era apartment block in Skopje, Macedonia.

National Bank of Macedonia, Skopje. Architects Radomir Lalovic and Olga Papes, 1975.

National Bank of Macedonia, Skopje. Architects Radomir Lalovic and Olga Papes, 1975.

Great period-perfect sculpture in a park next to the Macedonian National Radio and Television building, Skopje

Great period-perfect sculpture in a park next to the Macedonian National Radio and Television building, Skopje

Glavna Posta – the Central Post Office of Skopje (stage 2). Architect Janko Konstantinov, 1982.

Glavna Posta – the Central Post Office of Skopje (stage 2). Architect Janko Konstantinov, 1982.

Central train station platform in Skopje, Macedonia.

Central train station platform in Skopje, Macedonia.

With a population of around half a million, Skopje would be considered a small city. In its compact layout, it holds more brutal architecture than any other comparable city on Earth. It doesn’t have the suburban fields of concrete apartment buildings found in the “Blokovi” of Novi Beograd in Serbia, or to a lesser degree Novi Zagreb in Croatia, but the depth of architectural brutalism in Skopje is perhaps more astounding. Almost all of the buildings featured are all easily accessible, located either right in the center of the city, or within a few minutes of it.

You're planning on travelling soon?

I personally use these sites to book my accommodation (lowest prices and best deals):

Agoda - this link will guarantee you the lowest price on hotels and apartments.

Booking.com - my current favourite - a great range of apartments and budget hotels, worldwide.

Wherever in the world you are headed to - here or somewhere else - book using these links and you'll get the best price. Nate.

Unfortunately, the Macedonian authorities do not share the same love of this contemporary architectural heritage. Many of the brutal and modern buildings of the communist era remain in government hands, and yet many are being allowed to decay. It won’t be long before some are past the point of no return. In a country that is suffering horrendous unemployment, you could be excused for thinking that the not-exactly-wealthy Macedonian government simply doesn’t have the time, resources, or money to maintain these buildings. However, this is not the case.

Skopje is currently in the thick of a construction boom. Museums, upgrades to Parliament House, decorative bridges, and more are being constructed everywhere. There are hundreds of bronze statues being erected all over the city center. I have never seen so many statues in one city. This initiative is all about Macedonian identity. The issues are deep, and the history is complex, but essentially the government has decided to prioritise, create, and invest in the ancient/historical Macedonian identity – at the expense of maintaining the absolutely unique and contemporary stock of buildings that were created in the second half of the 20th century.

Nikola Karev High School, Skopje Macedonia. Architect – Janko Konstantinov, 1968.

Nikola Karev High School, Skopje Macedonia. Architect – Janko Konstantinov, 1968.

Glavna Posta – the Central Post Office of Skopje (stage 1). Architect Janko Konstantinov, 1974.

Glavna Posta – the Central Post Office of Skopje (stage 1). Architect Janko Konstantinov, 1974.

Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music, 1974.

Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music, 1974.

GTC shopping mall, Skopje Macedonia. Architect – Živko Popovski, 1973

GTC shopping mall, Skopje Macedonia. Architect – Živko Popovski, 1973

Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts. Architect – Boris Čipan, 1976.

Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts. Architect – Boris Čipan, 1976.

Overview of the purely brutal, communist-era architecture of the Skopje post office complex.

Overview of the purely brutal, communist-era architecture of the Skopje post office complex.

Brutal students dormitory buildings “Goce Delčev” in Skopje, Macedonia. Architect – Georgi Konstantinovski, 1975.

Brutal students dormitory buildings “Goce Delčev” in Skopje, Macedonia. Architect – Georgi Konstantinovski, 1975.

Typical architecture of communist era Skopje. And, my home for a couple of weeks. Skopje, Macedonia.

Typical architecture of communist era Skopje. And, my home for a couple of weeks. Skopje, Macedonia.

Saint Kliment Cathedral. Architect Slavko Brezovski, 1972.

Saint Kliment Cathedral. Architect Slavko Brezovski, 1972.

Under the raw concrete, is dark wood paneling. Skopje State Hydrometeorological Institute. Architect – Krsto Todorovski, 1975.

Under the raw concrete, is dark wood paneling. Skopje State Hydrometeorological Institute. Architect – Krsto Todorovski, 1975.

More raw concrete and wood paneling. Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music, 1974.

More raw concrete and wood paneling. Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music, 1974.

The model for the rebuilding of Skopje. So futuristic, even in the 1960′s.

The model for the rebuilding of Skopje. So futuristic, even in the 1960′s.

I’m not entirely sure what the point of the new Las Vegas/Disneyland-esque government sponsored construction drive is. For such a small city, it’s an extreme, and costly, effort. Skopje’s locals are divided, but I think it’s safe to say most are against the government spending such large sums of money on what is a fairly kitsch effort at creating a national identity. It’s hard not to draw comparisons back to the propagandish era of communist Yugoslavia. The architecture itself is perhaps best described as tacky, albeit grand. However, tastes vary, and they change – and Skopje’s new architecture may yet prove to be a hit with tourists. Only time will tell.

Yugoslavia in the 1960′s must have been a truly fascinating place. Skopje, in 2013, is definitely a fascinating place. The city center holds concrete masterpieces sitting alongside every possible era of architecture from the last two millennium. An ancient Castle fortress looks down from one side, and the worlds biggest cross sits atop an inner city mountain on the other. On one side of the Vardar river that cuts through the city center, is a ancient neighbourhood that could be straight out of Istanbul. On the other, the city square with an enormous “Man On a Horse” statue (just don’t say it’s Alexander the Great, believe me) is a pleasurable and walk-able area normally bustling with activity. Connecting the two areas, is the Stone Bridge, built about 700 years ago – on top of much older Roman foundations. The layers and the contrast is unique for any city of this size.

I love this city. If you visit Skopje, I’m pretty sure you’ll love it to. It’s changing very fast at the moment. You could visit Skopje now, or in a few years when the construction dust has settled. Either way, it has something for everyone, is inexpensive, the locals are friendly, and you will just not believe your eyes when you get here.

And despite what this this collection of photos is telling you, Skopje is far more than just a communist era brutal concrete wonderland.

Nate

PS, I have a lot more photos of buildings that I haven’t covered – particularly the more “modernist” examples. If you’re on Facebook, you would have seen a few of these photos already. And, a video of me, in the shower of my spectacularly uncharacteristically luxury apartment. I’m sorry, it’s true. Check it out here.

PPS, this week I will be back in Belgrade. Just regaining some strength – with Croatia, Serbia, Albania, and Macedonia down – I’m not finished with the Balkans yet. Join the many people that get their posts by email, just pop your address in below. No spam, ever.

Nate Robert in #Macedonia May 6, 2013 Comments { 20 }

Skopje, capital city of Macedonia, is a dream world for lovers of cosmic concrete communist-era architecture. There is a reason that no other city on Earth has as many examples of brutalist architecture. There’s no tactful way to say this – the abundance of magnificent structures, is all due to a catastrophic earthquake that killed over 2000 people, and destroyed more than half of the buildings in this ancient city. In 1963, Skopje was flattened. In 1965, Japanese architect Kenzo Tange was selected as the winner of an international competition to redesign, and rebuild the city centre.

Napier – the small New Zealand city where my travelling partner Phillipa was born, suffered a similar fate. The great quake of Napier in 1931 occurred right at the peak of the Art Deco movement. Napier was destroyed, and then rebuilt, all in the early 1930′s. As a result, the city can rightfully claim the title of “art deco capital of the world”. Back in Skopje, 1963, the architectural trend wasn’t art-deco, it was modernist, with a particular focus on concrete brutalism. Unlike Napier, Skopje has yet to capitalise on its architectural heritage. I would suggest a new tourist slogan – “Skopje – Brutalist Capital of the World”. Perhaps it’s not as catchy.

Examples of brutalist architecture - a style typified by geometric themes and raw concrete – occur all over the formerly communist area of Yugoslavia. In Zagreb, in Belgrade, and in nearly every small town, exist examples from this era. However, it is the legacy of Kenzo Tange, that makes Skopje so special in this regard. Locals are indifferent about memories of the Yugoslavia communist-era in general, however most people I have spoken to when visiting these buildings are familiar with Kenzo Tange. And whether they are particularly a fan of this style of architecture or not is beside the point – it’s clear that the positive impact Kenzo Tange had on the community of Skopje, in the wake of a devastating natural event, will not soon be forgotten.

The brutal home of the Skopje State Hydrometeorological Institute. Architect – Krsto Todorovski, 1975.

The brutal home of the Skopje State Hydrometeorological Institute. Architect – Krsto Todorovski, 1975. Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music,1974.

Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music,1974. Brutal students dormitory buildings “Goce Delčev” in Skopje, Macedonia. Architect – Georgi Konstantinovski, 1975.

Brutal students dormitory buildings “Goce Delčev” in Skopje, Macedonia. Architect – Georgi Konstantinovski, 1975. Macedonian National Radio and Television building, Skopje. Architect – Kiril Acevski, 1971-1983.

Macedonian National Radio and Television building, Skopje. Architect – Kiril Acevski, 1971-1983. Looking up inside Universal Hall, Skopje, Macedonia. Prefabricated by the Bulgarian company Tehnoeksportstroj, completed in 1966. A donation to Macedonia.

Looking up inside Universal Hall, Skopje, Macedonia. Prefabricated by the Bulgarian company Tehnoeksportstroj, completed in 1966. A donation to Macedonia.And this is the part of the article where we deal with some problems of terminology. Macedonia, officially “The Republic of Macedonia” or “The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” depending on which international body you are speaking to, declared independence from communist Yugoslavia in 1991. The naming issue is telling, for a country whose government is seemingly hell bent on rebuilding its history (some people would say rewriting history), even the name of the country may not be final.

Due to a dispute with Greece, and in particular the Greek region just across the shared border also known as Macedonia, The Republic of Macedonia was admitted to the United Nations only with the provisional name of FYROM. But this soviet-esque abbreviation is already out of favor with many UN members. Apologies to Greece, but it appears the name FYROM will be going the same way as Rhodesia, The Dutch East Indies, and Upper Volta. To most people around the world, Macedonia, is Macedonia.

Brutalist, Modernist, But Not Communist Architecture?

Macedonian naming issues aside, there is another problem when referring to this style of architecture. Of course, it isn’t “communist architecture”. Kenzo Tange was certainly not communist, for a start. However, the fact remains that all of the architecture featured in this article, was indeed constructed during a period in which Macedonia was a part of communist Yugoslavia. I should also add that the Yugoslavian dictator Tito ruled his nation seemingly benevolently. There was no Iron Curtain in Yugoslavia, despite that this is the very region where the term originated. Much like China today, Yugoslavians were encouraged to be capitalist consumers. They didn’t suffer restrictions on leaving the country, as was occurring in much of the rest of Eastern Europe during this period.

Kenzo Tange and his Japanese team aside, the other architects of these structures may or may not have identified as communists, or socialists. The term is used these days, simply to denote a period in time. For westerners, the term communist architecture has come to denote the stark, efficient, cosmic, brutal, distinctive and unique style of Balkans area architecture that was often decidedly different from what was being built elsewhere. Personally, I think it’s a beautiful style. A venture into the interiors of any of these buildings will show that both form and function were frequently mastered.

Skopje State Hydrometeorological Institute. Architect – Krsto Todorovski, 1975.

Skopje State Hydrometeorological Institute. Architect – Krsto Todorovski, 1975. News Publishing Agency “Nova Makedonija” building (no longer used by this agency). Architect Blagoja Kolev, 1981.

News Publishing Agency “Nova Makedonija” building (no longer used by this agency). Architect Blagoja Kolev, 1981. Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music,1974.

Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music,1974. Typical concrete detail on a communist-era apartment block in Skopje, Macedonia.

Typical concrete detail on a communist-era apartment block in Skopje, Macedonia. National Bank of Macedonia, Skopje. Architects Radomir Lalovic and Olga Papes, 1975.

National Bank of Macedonia, Skopje. Architects Radomir Lalovic and Olga Papes, 1975. Great period-perfect sculpture in a park next to the Macedonian National Radio and Television building, Skopje

Great period-perfect sculpture in a park next to the Macedonian National Radio and Television building, Skopje Glavna Posta – the Central Post Office of Skopje (stage 2). Architect Janko Konstantinov, 1982.

Glavna Posta – the Central Post Office of Skopje (stage 2). Architect Janko Konstantinov, 1982. Central train station platform in Skopje, Macedonia.

Central train station platform in Skopje, Macedonia.With a population of around half a million, Skopje would be considered a small city. In its compact layout, it holds more brutal architecture than any other comparable city on Earth. It doesn’t have the suburban fields of concrete apartment buildings found in the “Blokovi” of Novi Beograd in Serbia, or to a lesser degree Novi Zagreb in Croatia, but the depth of architectural brutalism in Skopje is perhaps more astounding. Almost all of the buildings featured are all easily accessible, located either right in the center of the city, or within a few minutes of it.

You're planning on travelling soon?

I personally use these sites to book my accommodation (lowest prices and best deals):

Agoda - this link will guarantee you the lowest price on hotels and apartments.

Booking.com - my current favourite - a great range of apartments and budget hotels, worldwide.

Wherever in the world you are headed to - here or somewhere else - book using these links and you'll get the best price. Nate.

Unfortunately, the Macedonian authorities do not share the same love of this contemporary architectural heritage. Many of the brutal and modern buildings of the communist era remain in government hands, and yet many are being allowed to decay. It won’t be long before some are past the point of no return. In a country that is suffering horrendous unemployment, you could be excused for thinking that the not-exactly-wealthy Macedonian government simply doesn’t have the time, resources, or money to maintain these buildings. However, this is not the case.

Skopje is currently in the thick of a construction boom. Museums, upgrades to Parliament House, decorative bridges, and more are being constructed everywhere. There are hundreds of bronze statues being erected all over the city center. I have never seen so many statues in one city. This initiative is all about Macedonian identity. The issues are deep, and the history is complex, but essentially the government has decided to prioritise, create, and invest in the ancient/historical Macedonian identity – at the expense of maintaining the absolutely unique and contemporary stock of buildings that were created in the second half of the 20th century.

Nikola Karev High School, Skopje Macedonia. Architect – Janko Konstantinov, 1968.

Nikola Karev High School, Skopje Macedonia. Architect – Janko Konstantinov, 1968. Glavna Posta – the Central Post Office of Skopje (stage 1). Architect Janko Konstantinov, 1974.

Glavna Posta – the Central Post Office of Skopje (stage 1). Architect Janko Konstantinov, 1974. Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music, 1974.

Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music, 1974. GTC shopping mall, Skopje Macedonia. Architect – Živko Popovski, 1973

GTC shopping mall, Skopje Macedonia. Architect – Živko Popovski, 1973 Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts. Architect – Boris Čipan, 1976.

Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts. Architect – Boris Čipan, 1976. Overview of the purely brutal, communist-era architecture of the Skopje post office complex.

Overview of the purely brutal, communist-era architecture of the Skopje post office complex. Brutal students dormitory buildings “Goce Delčev” in Skopje, Macedonia. Architect – Georgi Konstantinovski, 1975.

Brutal students dormitory buildings “Goce Delčev” in Skopje, Macedonia. Architect – Georgi Konstantinovski, 1975. Typical architecture of communist era Skopje. And, my home for a couple of weeks. Skopje, Macedonia.

Typical architecture of communist era Skopje. And, my home for a couple of weeks. Skopje, Macedonia. Saint Kliment Cathedral. Architect Slavko Brezovski, 1972.

Saint Kliment Cathedral. Architect Slavko Brezovski, 1972. Under the raw concrete, is dark wood paneling. Skopje State Hydrometeorological Institute. Architect – Krsto Todorovski, 1975.

Under the raw concrete, is dark wood paneling. Skopje State Hydrometeorological Institute. Architect – Krsto Todorovski, 1975. More raw concrete and wood paneling. Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music, 1974.

More raw concrete and wood paneling. Saint Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Architect Marko Music, 1974.

The model for the rebuilding of Skopje. So futuristic, even in the 1960′s.

The model for the rebuilding of Skopje. So futuristic, even in the 1960′s.I’m not entirely sure what the point of the new Las Vegas/Disneyland-esque government sponsored construction drive is. For such a small city, it’s an extreme, and costly, effort. Skopje’s locals are divided, but I think it’s safe to say most are against the government spending such large sums of money on what is a fairly kitsch effort at creating a national identity. It’s hard not to draw comparisons back to the propagandish era of communist Yugoslavia. The architecture itself is perhaps best described as tacky, albeit grand. However, tastes vary, and they change – and Skopje’s new architecture may yet prove to be a hit with tourists. Only time will tell.

Yugoslavia in the 1960′s must have been a truly fascinating place. Skopje, in 2013, is definitely a fascinating place. The city center holds concrete masterpieces sitting alongside every possible era of architecture from the last two millennium. An ancient Castle fortress looks down from one side, and the worlds biggest cross sits atop an inner city mountain on the other. On one side of the Vardar river that cuts through the city center, is a ancient neighbourhood that could be straight out of Istanbul. On the other, the city square with an enormous “Man On a Horse” statue (just don’t say it’s Alexander the Great, believe me) is a pleasurable and walk-able area normally bustling with activity. Connecting the two areas, is the Stone Bridge, built about 700 years ago – on top of much older Roman foundations. The layers and the contrast is unique for any city of this size.

I love this city. If you visit Skopje, I’m pretty sure you’ll love it to. It’s changing very fast at the moment. You could visit Skopje now, or in a few years when the construction dust has settled. Either way, it has something for everyone, is inexpensive, the locals are friendly, and you will just not believe your eyes when you get here.

And despite what this this collection of photos is telling you, Skopje is far more than just a communist era brutal concrete wonderland.

Nate

PS, I have a lot more photos of buildings that I haven’t covered – particularly the more “modernist” examples. If you’re on Facebook, you would have seen a few of these photos already. And, a video of me, in the shower of my spectacularly uncharacteristically luxury apartment. I’m sorry, it’s true. Check it out here.

PPS, this week I will be back in Belgrade. Just regaining some strength – with Croatia, Serbia, Albania, and Macedonia down – I’m not finished with the Balkans yet. Join the many people that get their posts by email, just pop your address in below. No spam, ever.

M

Mirditor

Guest

[h=3]Skulpturen-Wahn in Skopje[/h]Mazedonien ist eines der ärmsten Länder Europas. Dennoch baut die Regierung zahllose Statuen und Plastiken mythischer slawischer Helden. Ohne Zögern werden Figuren wie Alexander der Große vereinnahmt. Minderheiten im Land, wie die Albaner, kommen in dieser Fantasiewelt dagegen nicht vor.

Videoblog: Skulpturen-Wahn in Skopje | tagesschau.de

Videoblog: Skulpturen-Wahn in Skopje | tagesschau.de

ZX 7R

Glatzen- und Zollstockentwicklerosoarcher

Skulpturen-Wahn in Skopje

Mazedonien ist eines der ärmsten Länder Europas. Dennoch baut die Regierung zahllose Statuen und Plastiken mythischer slawischer Helden. Ohne Zögern werden Figuren wie Alexander der Große vereinnahmt. Minderheiten im Land, wie die Albaner, kommen in dieser Fantasiewelt dagegen nicht vor.

Videoblog: Skulpturen-Wahn in Skopje | tagesschau.de

Mal schauen, ob Deins auch im Müll landet wie meins!

VardarSkopje

Spitzen-Poster

Mal schauen, ob Deins auch im Müll landet wie meins!

Wieso auch nicht ? Der Scheiß wird hier auf jeder Seite gepostet.

App installieren

So wird die App in iOS installiert

Folge dem Video um zu sehen, wie unsere Website als Web-App auf dem Startbildschirm installiert werden kann.

Anmerkung: Diese Funktion ist in einigen Browsern möglicherweise nicht verfügbar.